Disordered Eating vs Eating Disorder: How to Differentiate the Two

The terms "disordered eating" and "eating disorder" are often used interchangeably—but they represent distinct concepts that impact someone’s physical and mental health.

Living in a world saturated with diet culture and body image pressures, it's not surprising that we’re hearing more and more about these topics. Many people struggle with one or the other, often without even knowing it or ever getting help.

This is why it’s sadly not shocking that 22 percent of children and adolescents globally suffer from disordered eating. Plus, eating disorders in teens and young adults at least doubled during COVID.

What’s clear is that children, teens, young adults, and adults alike are struggling with their relationship to food and their body, in ways that are recognized as diagnosable and not.

If this is you, or someone you know, it can be helpful to understand the nuances that distinguish disordered eating vs eating disorder and how to get support.

Understanding Disordered Eating

Disordered eating encompasses a range of irregular eating behaviors that may not meet the clinical criteria for an eating disorder but still severely impact health and quality of life. It involves a dysfunctional relationship with food, body image, and weight, often characterized by restrictive dieting, binge eating, or purging behaviors.

One common example of disordered eating is chronic dieting. Many individuals, particularly in our image-focused, social-media-obsessed world, are caught in a cycle of restrictive eating patterns fueled by the pursuit of an idealized body image. This might involve skipping meals, severely limiting calorie intake, or engaging in fad diets that promise quick results.

What makes this difficult is that these behaviors are often praised. Masked as “wellness,” those who are suffering may actually be told they’re doing a great job or have “amazing willpower.” This reinforces the behavior and keeps those suffering stuck in the cycle of disordered eating.

Even more difficult is that those of us who struggle with disordered eating often do it in silence. The anxiety, fear, and exhaustion can’t be seen on the surface. I shared my personal experience with this in an Instagram post during EDAW 2024.

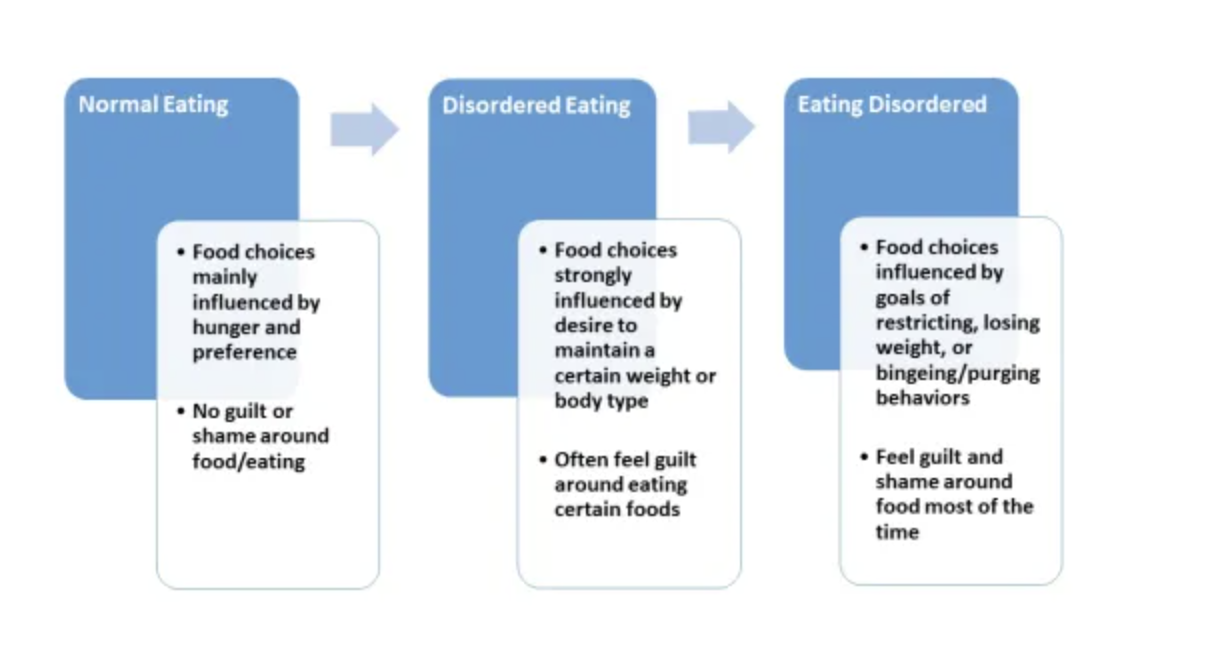

Disordered Eating Spectrum

It's important to recognize that disordered eating exists on a spectrum, and behaviors can vary in intensity and frequency. While occasional dieting or occasional overeating or eating past fullness, may not necessarily indicate a problem, persistent patterns of disrupted eating behaviors can signal underlying issues that warrant attention and support.

The graphic below, from The Columbia Center for Eating Disorders, is a good visual explanation of this spectrum.

Disordered Eating Examples

Because disordered eating is often seen as the pursuit of “health and wellness”— it can be hard to know where you fall and if your behaviors are disordered. One of the most important questions to ask yourself if you’re not sure whether your eating is disordered is: Why am I engaging in this behavior? What is the intention?

If the honest answer is to control your body size or weight, or some version of that, it’s likely the result of a disordered relationship with food and your body. To help you gain some clarity, here are some more examples of disordered eating:

Chronic Dieting: Constantly following restrictive eating patterns or following fad diets in pursuit of weight loss.

Skipping Meals: Intentionally avoiding meals or snacks to manage or control your calorie intake.

Counting Calories Obsessively: Constantly monitoring and restricting calorie intake to an unhealthy extent, whether for a one-time event or chronically.

Eliminating Food Groups: Cutting out entire food groups (e.g., carbs, fats) without medical necessity or balanced substitution.

Eating in Secret: Consuming food in private and hiding eating habits from others because you feel ashamed or guilty.

Excessive Exercise: Compulsively engaging in intense or prolonged exercise regimens to burn calories or compensate for eating.

Food Restriction: Severely limiting portion sizes or types of food consumed, leading to nutritional deficiencies and imbalances.

Preoccupation with Food: Constantly thinking about food, meal planning, or obsessing over caloric content and nutritional value. A good example of this is cooking all your own food, even when going to events or get-togethers to control every aspect of what you eat.

Rigid Eating Schedule: Adhering strictly to specific meal times and rituals and feeling anxious or stressed if you have to deviate from that schedule.

Avoiding Social Situations Involving Food: Withdrawing from social gatherings or events because you’re worried about being tempted to eat "forbidden" foods or losing control and eating “too much.”

Using Food as a Reward or Punishment: Associating food with emotional rewards or punishments, such as restricting food after "bad" behavior or using food as a coping mechanism.

Compulsive Eating: Consuming large quantities of food rapidly and uncontrollably, often to the point of discomfort or distress. This is a common biological response to restriction, called the Binge-Restrict Cycle.

Obsessive Weighing: Frequently weighing oneself and becoming hyper-fixated on any fluctuations in weight, no matter how small.

Compensating After Overeating: Engaging in compensatory behaviors (e.g., fasting, excessive exercise) following episodes of overeating, even if they are infrequent.

Dietary Supplements Abuse: Relying excessively on dietary supplements or weight loss products as a quick fix for achieving desired body image.

Self-Criticism: Harshly judging yourself based on food choices, body weight, or perceived failures in maintaining your dietary goals.

Emotional Eating: Chronically turning to food as a way to cope with stress, anxiety, sadness, or other emotions, rather than addressing the underlying issues.

Body Checking: Frequently examining your body in mirrors and photos. This might include pinching skin, hyper-focusing on “problem areas” or measuring body parts to monitor weight or appearance. Check out this body-checking blog post from Brave Space Nutrition to learn more about what body-checking is.

Grazing or Snacking Constantly: Eating small amounts of food frequently throughout the day, often without regard for hunger or fullness cues.

Orthorexia: Developing an obsession with "clean" or "pure" eating, fixating on consuming only foods deemed healthy or virtuous while demonizing others as "unhealthy" or "impure." It’s estimated that 21 to 57 percent of the general population engage in orthorexic behaviors.

Recognizing Eating Disorders

Eating disorders are clinically diagnosed mental health conditions characterized by severe disturbances in eating behaviors and emotions related to food and body image.

Unlike disordered eating, eating disorders involve established, chronic, and pervasive patterns of behavior that significantly impact an individual's physical and psychological well-being.

Those with diagnosable eating disorders can be suffering from significant physical harm, including malnutrition, dehydration, GI issues, and electrolyte imbalance. Many people don’t know that someone dies from an eating disorder every 52 seconds. It’s the second most fatal mental illness, second only to Opioid Use Disorder.

Eating Disorder Diagnoses

There are many clinical diagnoses for eating disorders depending on the symptoms exhibited. Most often, multiple disorders are being experienced at one time. One of the least known, but most common eating disorders is Binge Eating Disorder (BED).

This involves recurrent episodes of uncontrollable overeating, without the compensatory behaviors seen in bulimia. Individuals with binge eating disorder may consume large quantities of food in a short period, often feeling a loss of control during episodes and experiencing distress afterward.

Conversely, one of the most well-known eating disorders is anorexia nervosa, which involves extreme calorie restriction and an intense fear of gaining weight, often accompanied by a distorted body image. Individuals with anorexia may:

Engage in excessive exercise

Meticulously control their food intake

Exhibit physical symptoms such as rapid weight loss, fatigue, and dizziness

Bulimia nervosa is another common eating disorder marked by episodes of binge eating followed by purging behaviors, such as self-induced vomiting or misuse of laxatives.

Despite attempts to compensate for overeating, individuals with bulimia often feel a sense of shame and guilt about their eating habits, which perpetuates the cycle of bingeing and purging. Bulimia can also present as extreme over-exercise, a form of purging through “working off” the food one eats.

Check out our full list of all diagnosable eating disorders, which also includes:

Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED)

Unspecified Feeding or Eating Disorder (UFED)

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

Differentiating Between the Two

While disordered eating and eating disorders share some similarities, there are key distinctions that can help differentiate between the two. Please remember that this is rarely a this or that situation—and you don’t need to have “eating disorder symptoms” to seek help.

Severity of Symptoms

Disordered eating typically refers to a wide range of irregular eating behaviors that may not meet the diagnostic criteria for an eating disorder.

While disordered eating can still have negative effects on physical and mental health, the severity and impact are generally less severe compared to a diagnosed eating disorder.

Eating disorders, on the other hand, are clinically diagnosed mental health conditions characterized by severely disordered eating behavior, body image, and weight regulation.

A diagnosed eating disorder can dangerously impact an individual's physical health, emotional well-being, and overall quality of life, and may require professional intervention for treatment.

Clinical Diagnosis

Disordered eating lacks the specific diagnostic criteria outlined in the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) used by health professionals for diagnosing eating disorders.

Instead, disordered eating encompasses a broader spectrum of behaviors that may not meet the threshold for a clinical diagnosis.

Eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder, have well-defined diagnostic criteria involving specific patterns of disordered eating behavior, along with associated psychological and physiological symptoms, which must be met for a formal diagnosis.

The DSM does have limitations, however, and can often be a barrier to someone with severe eating disruptions who does not present in the ways outlined by clinical criteria.

The criteria for whether an eating disorder is “diagnosable” is not inclusive, which means doctors overlook many people who need that diagnosis to get formal treatment. This includes people in larger bodies, those in the BIPOC community, trans or queer folks, and other marginalized populations.

This, among other issues including financial obstacles, means that many people are never diagnosed who might meet clinical criteria – or who simply need help preventing their behaviors from worsening. Additionally, early detection and diagnosis are critical to addressing widespread disordered eating and helping more people access healing.

Frequency and Duration

Disordered eating behaviors may occur sporadically or intermittently and may not persist over time. They could be triggered by various factors such as stress, social pressures, or changes in routine.

Eating disorders typically involve persistent and recurrent patterns of disordered eating behaviors that endure over an extended period, often for months or years.

These behaviors become ingrained and entrenched, significantly impacting the individual's daily life and functioning.

While this distinction may be true in a lot of cases, frequency and duration are areas where disordered eating and eating disorders are more similar than not.

People can suffer from both disorders in different ways, at different times of life, for decades, without realizing it as such.

Seeking Support and Treatment

Regardless of whether you or someone you know is struggling with disordered eating or an eating disorder, seeking support from qualified professionals is essential for recovery and healing. If your relationship with food or your body is negatively impacting your life, it will be helpful to seek help.

Therapy, nutritional counseling, and medical intervention can all be used to support healing, regardless of where on the spectrum your concerns may fall. Here are some resources if you or someone you know are ready for help:

Disordered Eating vs Eating Disorder: Different But Similar

While disordered eating and eating disorders are different in many ways, both can impact mental and physical health—and be incredibly difficult to live with. By understanding the differences between the two and recognizing the signs and symptoms, we can better support ourselves and others in cultivating a better relationship with food and body image.

Please remember, you’re never “not sick enough” to get help. If you’re struggling and it’s impacting your life, you deserve to get help and support in whatever way you need.